http://www.japanfocus.org/-Gwyn-Kirk/3356

Fortress Guam: Resistance to US Military Mega-Buildup

LisaLinda Natividad and Gwyn Kirk

United States presidents rarely visit the U.S. territory of Guam (or Guåhan in the Chamorro language), but President Obama may visit in June 2010. This will be a significant stop for residents of this small island, 30 miles long and eight miles wide, dubbed, “Where America’s day begins.” Guam is the southern-most island in the Northern Mariana chain that also includes Rota, Tinian, and Saipan. It is the homeland of indigenous Chamorro people whose ancestors first came to the islands nearly 4,000 years ago. Formed from two volcanoes, Guam’s rocky core now constitutes an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” for the United States military in the words of Brig. Gen. Douglas H. Owens, a former commanding officer of Guam’s Andersen Air Force Base.1

The reason given for Obama’s unprecedented visit to the island in a White House Conference call by Ben Rhodes, Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communications, is this:

While there he’ll not only visit with commanders but also with local Guam authorities. And he’s going to make sure that we have a very realistic and sustainable and well thought out approach to Guam. He has a vision which we refer to here as “one Guam, green Guam,” which is apropos of many of the questions heretofore, designed to make sure that we’re investing in capabilities on Guam that are sustainable over the course of time, that are clean energy focused, that do take very concrete steps to reduce the high price of energy on the island, and obviously will lead to an end state that’s politically, operationally, and environmentally sustainable.

So the President, while there, will also take a hard look at the project and infrastructure needs on Guam. We’ll obviously be looking at base-related construction that must take into accounts(sic) the needs of not only of an increased troop presence or Marine presence, but also the needs of the people of Guam, the impact on the environment, and the important role that the United States plays within the region… I’d rather just make clear that we have a commitment to the people of Guam, and that as part of our ongoing plan for our presence in the region, are going to make very common-sense and important investments in the infrastructure there.2

Barely mentioned in the shadows of these fine words with their emphasis on sustainability, are the real reasons for Obama’s visit: to rally community and official support for the Department of Defense plan to relocate 8,600 Marines from Okinawa (Japan) to Guam, provide additional live-fire training sites, expand Andersen Air Force Base, create berthing for a nuclear aircraft carrier, and erect a missile defense system on the island.

Military Bases on Guam 1991

Despite their economic dependence on the U.S. military, which occupies one-third of the island’s landmass and dominates the island’s economy, people in Guam have expressed strong opposition to the proposed enormous increase in the US military presence on economic, environmental, and cultural grounds. Due to Guam’s status as an unincorporated U.S. territory, however, local communities are highly constrained in their ability to influence the political process. Indeed, they were not even consulted when the expansion plans were developed. Jon Blas of the coalition We Are Guahan stated, “We have not been able to say yes or no to this. Hawaii said no. California said no. But we were never given the opportunity.”3 After more than a century of U.S. control, the justification of military development for purposes of “national security” has been widely accepted by most island residents, many of who rely on the military for jobs given the lack of alternative employment. However, following the release of the DOD’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) in November 2009, which for the first time revealed details of the proposed military build-up, community members started to question the enormous sacrifices they are being ordered to make in the name of “national security”.

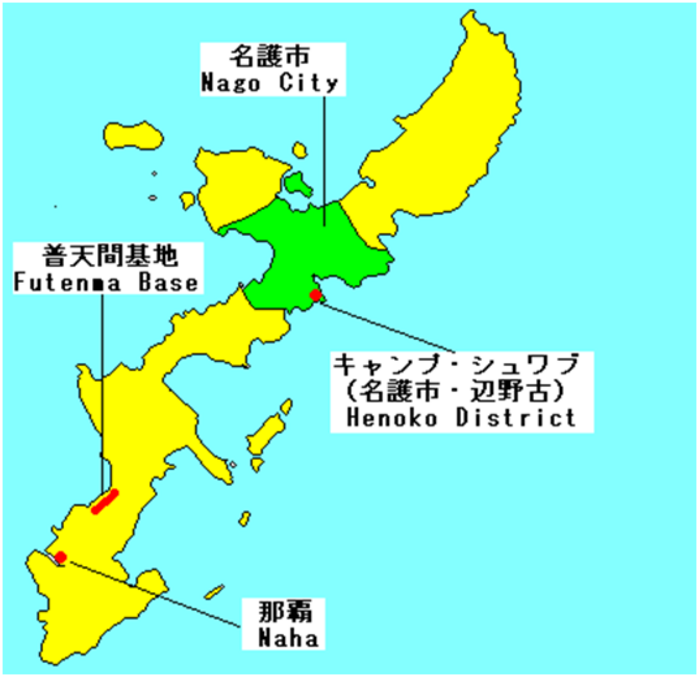

The situation is complicated by the fact that the United States proposal is contingent on the willingness of the recently elected Democratic Party government of Japan to honor the previous administration’s agreement to relocate an established U.S. Marines base from a dense urban area in Okinawa to a new facility on a coastal site at Henoko in northern Okinawa. The former Japanese government had agreed to contribute $6 billion towards construction of the Henoko base and the relocation of Marines to Guam. The incoming coalition government was successful at the polls partly due to campaign commitments to review the U.S.-Japan military alliance in general, and the base construction in particular. Some members criticized Japan’s acquiescence toward U.S. foreign policy; others resented the U.S. “occupation mentality.”4

Defense Secretary Robert Gates and President Obama made hasty visits to Tokyo last fall, invoking the importance of the alliance and pressing to keep the Okinawa-Guam accord intact. Indicative of the turn in opinion, some Japanese media bridled at this “bullying” and “high-handed treatment.” Prime Minister Hatoyama announced that his government would make its decision on the Futenma relocation issue by December 2009, later deferring a response until May 2010. In a March 3rd interview with the Asahi Shimbun, Richard P. Lawless, former deputy undersecretary of Defense for Asia-Pacific affairs, who was involved in negotiating the agreement with Japan, expressed frustration that “the Japanese government seems intent on playing domestic politics and doesn’t fully understand the magnitude of the issue.”5 Under steady US pressure, the Hatoyama government in early May abandoned its resistance to the Henoko plan. The question remains, however, whether it is prepared to impose its will on an Okinawan population which strongly opposes the new base. Meanwhile, Guam’s Congressional representative, Madeleine Bordallo, who fervently supported the military build-up as the primary way to boost Guam’s weak economy has moderated her position with a range of stipulations as a result of the outpouring of pubic testimony at town hall meetings, public hearings, community events, and in media reports. This article examines the issues of base expansion on Guam and assesses the movement against military expansion on Guam.

History of Guam

Archeological evidence indicates that Guam’s indigenous Chamorro people first arrived in these islands around 2,000 BCE. Chamorros lived in coastal villages where they fished, farmed, and hunted to sustain themselves. They were skilled navigators who traded throughout Micronesia. The arrival of Ferdinand Magellan in the Marianas in 1521 marked the first contact with the western world. In 1565, Spain sent an expedition to claim Guam for the Spanish Crown and in 1668 Father Diego Luis de San Vitores started a Catholic mission. This foreign influence, with attendant violence and epidemics of diseases, decimated the local population.

|

Latte stones, the foundations of Chamorro homes from 500 A.D.

|

For 250 years, Spanish galleons plied between Asia, Europe and the Americas, carrying silks, spices, porcelain, cotton, and ivory from Manila to Acapulco, the viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico). These goods were then transported overland to Vera Cruz and loaded onto ships for Spain. On the return journey, cargo included Mexican silver, Spanish administrators, missionaries, and provisions for the garrison in the Marianas. En route from Acapulco, the vessels replenished supplies of food and water on Rota and Guam.6

Spain remained Guam’s colonizer until the conclusion of the Spanish-American War. Under the terms of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines were ceded to the United States. Spain sold the Northern Mariana Islands and the Caroline Islands to Germany, thus separating Guam politically and culturally from neighboring islands in the Marianas and throughout Micronesia. President McKinley placed Guam under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Navy, which used the island as a refueling and communications station. During this time, Naval admirals served as governors and most administered the island as though they were running a ship.7 The Naval administration also regulated land acquisition, the sale of liquor, marriages, taxation, agriculture, and schooling. An old military plan to put Chamorro people on reservations in the north and south of the island, leaving two-thirds of the land for military use, did not materialize.8 However, people’s demand for citizenship was denied as an encroachment on military control.9

On December 8, 1941, Japanese warplanes bombed U.S. military installations on Guam, the same day as the attack on Pearl Harbor. Japanese forces took the island two days later and renamed it “Omiya Jima”.10 For 31 months the people of Guam were subjected to hardship and atrocities inflicted by the Japanese Imperial Army; including forced labor to build runways, incarceration in concentration camps (such as Manenggon), executions, slaughter, forced prostitution, and rape. Chamorros resisted the Japanese invasion and, in allegiance to the U.S., assisted in hiding an American soldier, George Tweed, from Japanese forces for the entire occupation period. Recollections of World War II experiences evoke tears and trauma memories for most war survivors to this day.11

Hailed as “liberation forces,” U.S. troops landed on Guam on July 21, 1944 after thirteen consecutive days of naval bombardment in which thousands lost their lives.

|

Planting the US flag on Guam

|

The bombing, followed by fierce combat, ravaged the island, and the main city of Hagatna was virtually destroyed. As soon as the U.S. military secured Guam, they turned the island into a strategic forward base for the final push toward Japan. As was occurring in Okinawa at approximately the same time, thousands of acres were taken for the construction of naval and air force facilities and many Chamorros were dispossessed of their ancestral clan lands (such as the village of Sumay) and moved to neighboring locations designated by the U.S. military.

Political and Economic Status

The Organic Act of Guam passed by the U.S. Congress in 1950 made Guam an unincorporated territory of the United States with limited self-governing authority. The Organic Act placed Guam under the administrative control of the Department of the Interior. With a current population of approximately 173,456, Guam is one of 16 non-self-governing territories listed by the United Nations, and represented by one non-voting delegate in the U.S. Congress. Residents are U.S. citizens but not entitled to vote in presidential elections. Federal-territorial policies are decided in Washington, 7,938 miles away, placing a number of restrictions on the island and hampering the development of a viable civilian economy.

Prior to WWII, Guam was self-sufficient in agriculture, fishing, hunting, and husbandry. US Naval administrators encouraged food production for local and military needs.12 Nearly every family grew vegetables and produced meat; some specialized in fishing; and there was a viable copra industry.13 Following World War II, the military took a large portion of arable land to build bases and other installations, equivalent to nearly 50 percent of the island’s landmass, including some of the most fertile land near popular fishing grounds. Since then, some lands have been returned following civic protest, with the U.S. presently occupying nearly one-third of the island, part of which is not presently being used. Currently, nearly 90 percent of Guam’s food is imported.

The island’s economy is geared toward the military: both in support of the US military and in charting the career path for youth. The military is by far the major employer, with most families connected to someone serving in the military or employed to support military operations. There are three JROTC programs in the island’s public high schools, as well as an ROTC program at the University of Guam. According to Washington Post reporter Blaine Harden, “Guam ranked No. 1 in 2007 for recruiting success in the Army National Guard’s assessment of 54 states and territories.”14 A key reason for this is economic. Poverty rates on Guam are high, with 25% of the population defined as poor. Between 38% and 41% of the island’s population qualifies for Food Stamps. Wage rates are low; schools are underfunded; and there are few opportunities for technical training on the island. The fact that Guam was occupied by Japan during World War II is another issue in recruitment. Harden notes:

“People here grow up with war ringing in their ears—as described by their grandparents… ‘If there is a group of Americans who understand the price of freedom, we do,’ said Michael W. Cruz, lieutenant governor of Guam and a colonel in the Army National Guard. Cruz’s grandmother …was held in a concentration camp. She was forced to watch as Japanese soldiers chopped off the heads of her brother and her eldest son. Her eldest daughters were forced into prostitution.”15

Many young people yearn to leave “the rock” to continue their education, to find work, and to experience a wider world. Indeed, more Chamorros currently live outside Guam than on the island, a social indicator consistent with that of other indigenous peoples who have a colonial history.

The island’s infrastructure is poor. The only civilian hospital operates at 100% capacity three weeks out of the month and its school system struggles to meet payroll several times a year. The island’s water supply is barely adequate to sustain the current population and the only civilian landfill for trash disposal is nearly at full capacity. Government of Guam agencies that oversee education, mental health, substance abuse, and the landfill are currently under federal receivership, meaning that the federal government has hired an independent entity to take over certain functions of these agencies due to substandard conditions.

The other significant industry on Guam is tourism, mainly catering to visitors from Japan, Korea, and Taiwan on 3-4 day tours. Tour companies offer fishing trips, beach weddings, honeymoon suites, and golf courses (including a 24-hole course). Major hotels surround the beautiful Tumon Bay, a “mini Waikiki,” with name-brand stores, dance clubs, and strip clubs. Tourism provides sporadic, low-paying jobs for local people, but has declined in recent years due to economic recession, especially the weakness of the Japanese economy.

Fortress Pacific: Proposed Military Build-up

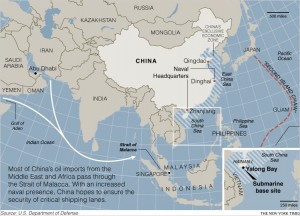

Guam’s military significance is being redefined as part of a major realignment and restructuring of U.S. forces and operations in the Asia-Pacific region. According to Captain Robert Lee, “We’re seeing a realignment of forces away from Cold War theatres to Pacific theatres and Guam is ideal for us because it is a US territory and therefore gives us maximum flexibility”.16 Much may be coded into the phrase “Pacific theaters”, but a key point is that Guam’s status as a U.S. territory gives military planners great freedom of operation without having to negotiate with another national government.

The proposal released by the Pacific Command in 2006, comprised several elements:

• Transfer of 8,000 Marines from Okinawa and 1,000 Army personnel from South Korea by 2014;

• Development of a Marine Corps base and training area;

• Expansion of Andersen AFB as part of the Global Strike Force, including home-based B52s, and rotation of B1 supersonic strike aircraft and B2 Stealth bombers from Hawaii, Alaska, and continental U.S.;

• Expansion of U.S. Naval Base, for submarines and aircraft carrier groups—already 3 nuclear-powered submarines are home-based, with 3 more subs planned. Expansion to include nuclear aircraft carrier transient operational capability (the U.S. military will have 6 of its 11 nuclear submarines in the Pacific by 2010); and

• Ballistic Missile Defense capability to intercept attack against assets.

|

Andersen Air Force Base

|

Described as the “largest project that the Department of Defense has ever attempted,17 this plan also defines Guam as a power projection hub, the “tip of the spear,” “Fortress Pacific,” and “America’s unsinkable aircraft carrier.” Commenting on this military investment, Admiral Johnson said: “Guam is no longer the trailer park of the Pacific. Guam has emerged from backwater status to the center of the radar screen. This is rapidly becoming a focus for logistics, for strategic planning.”18 He noted, “Guam also offers the Air Force’s largest fuel supply in the United States, its largest supply of weapons in the Pacific and a valuable urban training area in an abandoned housing area at a site known as Andersen South.”19

Addressing service members posted to Guam, a military website waxes enthusiastic about the pleasures of Guam for military personnel:

Have you received orders to Guam? … Forget what you have heard. You are heading to a true Pacific Island tropical paradise … Guam offers wide beaches, snorkeling and scuba diving, deep-sea sport fishing, world-class golf courses, lush tropical jungles and a rich cultural and historical heritage. The Commander Naval Region Marianas main base and Andersen Air Force Base each have large well stocked commissaries and exchanges, well equipped and managed Morale Welfare and Recreation clubs and facilities… private military beaches, a marina and other dedicated military recreational facilities… plus great dining and varied nightlife.20

Between 2006 and 2009, while Department of Defense contractors prepared a Draft Environmental Impact Statement as required under the National Environmental Policy Act, speculation was rife among business owners, elected leaders, and community members about the projected population increase, the economic impact of military expansion, and the consequences of the addition of tens of thousands of people on the already fragile and contaminated social and environmental infrastructure. Arguments in favor of the anticipated construction boom emphasized economic growth and the potential for expanded services and amenities. Opponents were skeptical about the much-touted economic advantages. They argued that the island lacks the environmental capacity for a major increase in population; that military-related personnel could outnumber the Chamorro population, currently 37% of the total; and that Guam’s status as an unincorporated territory and its dependence on the federal government makes it difficult for leaders to take an independent political position. Moreover, opponents criticized inadequate opportunities for public meetings and comment.

The voices of the Guam Chamber of Commerce and other business leaders have shaped public discussion. In their view, the militarization of the island is the only viable means to boost Guam’s weak economy. Contractors have been lining up—from Washington-DC, to Hawaii, the Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan—jockeying for a piece of the action. “On Capitol Hill, the conversation has been restricted to whether the jobs expected from the military construction should go to the mainland Americans, foreign workers or Guam residents,” commented Democracy Now reporter Juan Gonzalez.21 “But we rarely hear the voices and concerns of the indigenous people of Guam, who constitute over a third of the island’s population”. More recently, Chamorro human rights attorney, Julian Aguon, and Chamorro educator and poet, Melvin Won Pat-Borja, have articulated dissent to the planned build-up on Democracy Now in an effort to gain national and international support for their struggle.

When the military held Environmental Impact meetings in Guam, Saipan, and Tinian in April, 2007, some 800 people attended and over 900 comments were received. Concerns included social, economic and cultural factors, international safety, law enforcement, transportation and infrastructure issues, marine resources/ecology, air quality, water quality, and overloading limited resources and services. In January 2008, Congresswoman Donna Christensen from the Virgin Islands convened U.S. Congressional Hearings on Guam, on an invitation-only basis. Protests resulted in the inclusion of public testimony as an “addendum” to the official proceedings. A year later, the Joint Guam Program Office (JGPO) held public meetings. Far from responding to the concerns voiced during earlier hearings, the JGPO announced that the military planned to take additional lands, including 950 acres for a live firing range. Although people stated concerns, there were no recording devices to document community sentiment.

Organizers created educational spaces as a way to get information to the public, including “Beyond the Fence” a one-hour weekly public radio show. Faculty members at the University of Guam organized public forums for community education and discussion regarding the proposed build-up, including talks by Prof. Catherine Lutz, editor of Bases of Empire; former U.S. Army Colonel Ann Wright; and activists from Okinawa, mainland Japan, and Hawaii. In September 2009, the university hosted presentations by participants of the 7th International Network of Women Against Militarism conference, women who live with the effects of U.S. bases and military operations in their home communities. This included scholars and activists from Australia, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Republic of Belau (Palau), Hawaii, Japan, Marshall Islands, Okinawa, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, South Korea, and the continental United States.

At the international level, the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization is another venue for speaking out about the military proposals. Attending its October 2008 meeting, several Chamorro speakers expressed concern over the planned military expansion, arguing that this “hyper-militarization” poses grave threats to the Chamorro people’s right to self-determination as the influx of military personnel and their dependants could challenge locally established law creating a Commission on Decolonization and asserted their right to vote. This concern about self-determination is particularly grave in light of the absence of a system to ensure that military personnel and their families do not register to vote in two different jurisdictions. They also argued that increased militarization would devastate the environmental, social, physical and cultural health of Guam. A representative of the Chamoru Nation urged the U.N. committee to send representatives to the island to conduct an assessment of the current situation on the island’s people.22 A follow-up delegation was sent to the U.N. in 2009 and the next visit is planned for May 2010 bearing the same message and concerns.

U.S. Military Legacy to Guam

Opponents of the build-up have emphasized the negative impact of the U.S. military on Guam, manifested in poor health, radiation exposure, contaminated and toxic sites, curbing of traditional practices such as fishing, and major land takings, which started in the early 20th century. The incidence of cancer in Guam is high and Chamorros have significantly higher rates than other ethnic groups.23 Cancer mortality rates for 2003-2007 showed that Chamorro incidence rates from cancer of the mouth and pharynx, nasopharynx, lung and bronchus, cervix, uterus, and liver were all higher than U.S. rates.24 Chamorros living on Guam also have the highest incidence of diabetes compared to other ethnic groups, and this is about five times the overall U.S. rate.

The entire island was affected by toxic contamination following the “Bravo” hydrogen bomb test in the Marshall Islands in 1954.25 Up to twenty years later, from 1968 to 1974, Guam had higher yearly rainfall measures of strontium 90 compared to Majuro (Marshall Islands). In the 1970s, Guam’s Cocos Island lagoon was used to wash down ships contaminated with radiation that had been in the Marshall Islands as part of an attempt to clean up the islands. Guam’s representative, Madeleine Bordallo, introduced a bill in Congress in March 2009, to amend the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) to include the Territory of Guam in the list of affected “downwinder” areas with respect to atmospheric nuclear testing in Micronesia (HR 1630). In April 2010, Senator Tom Udall introduced an amendment to RECA with the inclusion of Guam for downwinders’ compensation. While these initiatives have been the priority of the Pacific Association for Radiation Survivors for over five years now, people on Guam have yet to receive compensation for their suffering. The territory currently qualifies for RECA compensation in the “onsite-participants” category but not for downwind exposure.

Andersen AFB has been a source of toxic contamination through dumpsites and leaching of chemicals into the underground aquifer beneath the base. Two dumpsites just outside the base at Urunao were found to contain antimony, arsenic, barium, cadmium, lead, manganese, dioxin, deteriorated ordnance and explosive, and PCBs.26 Other areas have been affected by Vietnam-war use of the defoliants Agent Orange and Agent Purple used for aerial spraying, which were stored in drums on island. Although many of the toxic sites on bases are being cleaned up, this is not necessarily the case for toxic sites outside the bases.

Draft Environmental Impact Statement

The Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) regarding the military build-up was released in November 2009, a nine-volume document totaling some 11,000 pages, to be absorbed and evaluated within a 90-day public comment period. In response, there was an outpouring of community concern expressed in town hall meetings, community events, and letters to the press. Despite its length, the DEIS scarcely addressed questions of social impact, and it contains significant contradictions and false findings that were exposed in public comments and in the media. Some stated plans contained in the DEIS were outright flawed, as admitted by a DOD consultant.

Several major concerns have been raised with respect to the following issues: the impact of up to nearly 80,000 additional people on land, infrastructure and services; the “acquisition” of 2,200 acres for military use; the impact of dredging 70 acres of vibrant coral reef for a nuclear aircraft carrier berth; and the extent to which the much-touted economic growth would benefit local communities.

Impacts of population increase. A top estimate for increased population is nearly 80,000, a 47 percent increase over current levels; including troops, support staff, contractors, family members, and foreign construction workers. Proponents emphasize that the construction workers constitute a transient labor force that will leave when their contracts are over. Others argue that some will stay, marry, have children, and hope to get other work, as happened during the last major period of military construction in the 1970s. These people will be an added burden on local services that are already stretched to capacity because they will be housed off-base, will not use on-base medical services, and will be consumers of the island’s infrastructural resources.

Impacts on land and ocean. The military seeks to acquire an additional 2,200 acres of private and public land, which would bring its land holdings to 40 percent of the island. Included in the lands ear-marked for acquisition is the oldest Chamorro village of Pagat, registered at the Department of Historic Preservation as an archaeological site, with ancient latte stones of great cultural significance. The Marines propose to use the higher land, above the historic site, for live fire training but seek to control the entire area, from the higher land down to the ocean, where there are beautiful beaches. This proposal, described as “sacrilege” by local people, would restrict their access to the site to just seven weeks out of the year. The military already has a live-fire range on Guam and also on Tinian, where it controls nearly two-thirds of the island through leases with the government of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Many community members argue that the military, which already controls a third of the land area of Guam, should stay within this existing “footprint”.

A key question is whether the DOD would purchase, lease, or use powers of eminent domain to acquire land identified in the DEIS. Addressing the Guam Legislature on February 16, 2010, Congresswoman Bordallo formally opposed the use of eminent domain for the acquisition of lands. Speaking of Nelson family clan land designated for acquisition, Gloria Nelson, former Director of the Department of Education, stated in a DOD-sponsored public hearing on the Marianas Build-Up, “I don’t want to talk about the market value of my land because my land is not on the market.”

Another highly controversial proposal is the creation of a berth for a nuclear aircraft carrier, which will involve the detonation and removal of 70 acres of vibrant coral reef in Apra Harbor. Environmentalists and local communities oppose this on the grounds that coral provides habitat for a rich diversity of marine life and is endangered worldwide. Environmentalists also question how the disposal of huge quantities of dredged material would affect ocean life and warn that such invasive dredging may spread contaminants that have been left undisturbed in deep-water areas of the harbor. Opposition to this plan has been expressed by the Guam Fishermen’s Cooperative and the U.S.-based Center for Biological Diversity. On February 24, 2010, Guam Senator Judith Guthertz wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Navy, Ray Mabus, reiterating her proposal that the existing fuel pier that has been used by the USS Kitty Hawk be used as the site for the additional berthing to avoid the proposed dredging of Apra Harbor. Such an alternative plan would avoid the destruction of acres of live coral.

Economic Costs and Benefits

Since the announcement of the relocation plan to transfer 8,000 Marines and their dependents from Okinawa to Guam, the general sentiment shared by the media and members of the island’s business community is that the transfer would stimulate the local economy. In January 2010, the Guam Chamber of Commerce published a white paper entitled, “An Opportunity that Benefits Us All: A Straightforward, Descriptive Paper on Why We Need the Military Buildup.” Among the benefits presented are opportunities for the creation of employment, fostering business and entrepreneurship, the generation of revenues, and the expansion of tourism.

The overall cost of the buildup has been estimated at $10-15 billion. The DEIS makes it clear that this money is solely for new military construction on existing bases, on newly acquired lands, or for the expansion of a road to connect the bases. The DEIS assumes that most construction jobs will go to contract workers from Hawaii, the Philippines, or other Pacific-island nations, who can be expected to send most of their earnings as remittances to families back home. Military personnel are likely to spend much of their money on-base.

An economist at the University of Guam, Claret Ruane, published a paper examining the macroeconomic multipliers used in the DEIS to compute projected economic growth as a result of the military buildup. It states, “…that economic studies that use Hawaii’s spending multiplier tend to present a rosier picture of the positive economic impacts of proposed changes.” Ruane recomputes the multiplier and suggests that while the DEIS reflects the highest gains at $1.08 billion in 2014, a more realistic estimate is $374 million in the same year. It is noteworthy that 2014 is the year with the highest expected impact on the Gross Island Product.

The Guam Economic Development Authority estimated costs to local government at around $1 billion although the governor has said this is more likely to be $2-3 billion. More recently, it has been reported that the island will need $3-4 billion to upgrade its utilities infrastructure. While grants have recently been awarded to the Government of Guam for infrastructural upgrades, they do not begin to cover the costs necessary for the anticipated population influx.

Additional negative impacts include increased noise, worse traffic congestion, and higher rental prices. As local people earn considerably less than military personnel, they will be crowded out of the rental market. Other potential problems include the likely increase in crime and prostitution, increased dependence on the U.S., and an undermining of Chamorro culture and right to self-determination.

Shift in Leadership Stance

Both Congressional Representative Bordallo and Governor Felix Camacho have wavered in their positions after hearing the outpouring of popular opinion. At the start of the DEIS process, Bordallo was quiet about concerns in the proposed DOD plan. After attending town hall meetings for two days where people passionately shared personal testimonies, she listed several significant stipulations in her address to the Guam Legislature on February 16, 2010 stating that she will do the following:

• support limiting all military expansion to Defense Department properties on island;

• oppose any federal effort to acquire additional land by eminent domain;

• challenge aircraft carrier berth plans that will result in significant loss of coral;

• call for increased federal assistance and a clear strategy for improving the island’s roads, schools, water and wastewater, and Guam’s only seaport to support the buildup;

• oppose drilling any new wells to accommodate the Marine relocation until an independent assessment is made about the capacity of the northern aquifer;

• argue that all contract workers must be housed on-base. Any proposal to house guest workers outside the gates must address their impact on civilian infrastructure such as water, wastewater and power.

• argue that all contract workers must use military health and other facilities. The study on the socioeconomic impacts of the buildup must be rewritten to address these impacts.

Nonetheless, Congresswoman Bordallo framed her remarks by reminding residents of the need to work together to address these challenges because of the buildup’s importance to the region. “We are not embarking on this buildup solely for economic reasons. We are doing this because we appreciate more than any other American community our liberation and our freedom and the sacrifices it will take to preserve that freedom for generations to come”.27

Congresswoman Bordallo met with Governor Felix Camacho and members of the Guam Legislature in February and March to reach a consensus on buildup issues. The Governor and Speaker Judith Won Pat both said Bordallo’s speech underscored their concerns.28 In addition, Bordallo and Camacho are now asking that the move of the Marines be spread out over a longer period of time to lessen its overall impact and in order to phase the financing.

Outside Guam, Senator Jim Webb, a member of the Senate Committee on Armed Services and Chair of the East Asia and Pacific Affairs Subcommittee of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, voiced agreement with some of these points. After visiting Guam to assess the build-up plan, he commented:

The U.S. military occupies or retains over one-third of the island’s territory, and I do not believe that additional lands should be acquired. If they must be acquired out of a national security interest, the U.S. government out of respect for the people of Guam should seek private arrangements for use of the land and not exercise its right of eminent domain.29

He noted “great concerns” about the plan to place live-fire ranges on Guam for Marine Corps training, and recommended that this be transferred to Tinian. Finally, he urged the government to provide “the civilian infrastructure and services needed to support an increased population on the island. The priorities include port modernization, water acquisition, wastewater treatment, healthcare, and schools.”30

In addition, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), charged with evaluating and commenting on federal projects that might harm the environment, gave the DOD’s DEIS a scathing review. The EPA’s unusually harsh critique has generated concern in Washington and the interest of New York Times and Washington Post reporters have given it increased media visibility.

In their 95-page analysis, EPA scientists’ main concerns are the inadequacies of DOD plans to address the water supply and wastewater treatment needs of the increased population, which “will result in unsatisfactory impacts to Guam’s existing substandard drinking water and wastewater infrastructure which may result in significant adverse public health impacts” and “unacceptable impacts to 71 acres of high quality coral reef ecosystem in Apra Harbor”.31

The DOD must consider all public comments on the DEIS, but the EPA cannot compel compliance. However, the EPA has already referred the DEIS to the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), a high-level federal interagency body that can make recommendations directly to the President as to whether a project should be abandoned or modified in cases where discussion is in process among the DOD, EPA, USDA, and Department of the Interior. Also, together with the Army Corps of Engineers, the EPA is authorized to grant or withhold permits for detonation of the coral. Many opponents of the build-up felt vindicated by the EPA’s review. Congresswoman Bordallo and acting Governor, Michael Cruz, also praised the critique and called on the DOD to address the concerns raised.32

One Guam, Two Guams

Many public comments on the DEIS focused on unequal amenities and opportunities inside and outside the military fencelines: military personnel have higher earning power than members of local communities; the military hospital and on-base schools have better facilities than the civilian hospital and public schools; water use by a larger military population is likely to result in shortages for local people; private military beaches deny local community access to their ancestral heritage. Some commentators refer to a double standard, the parallel existence of Two Guams; one opponent of the build-up called it an “apartheid” system.

In mid-March 2010, the White House, sensitive to the criticisms of the environmental impact statement, issued a press statement emphasizing the administration’s commitment to “One Guam, Green Guam”, quoted earlier, promising to balance the military’s needs with the concerns of local people, to promote renewable energy, and to reduce fuel and energy costs on the island. As detractors noted, this does not address people’s core concerns. Is it possible to undertake a vast military expansion with sensitivity to the environment and other critical issues?

Educating and Organizing

The gradual increase in education and organizing on Guam has resulted in an outpouring of public questioning and opposition. In turn, this has been instrumental in causing a shift in the positions of several key leaders, high-level discussion in Washington, and Obama’s plan to visit Guam in June 2010– a stop-over postponed from March due to the Congressional vote on healthcare reform.

Long-standing community connections and Chamorro cultural revival, with an emphasis on reclaiming history, language, literature, and ancient traditions, have been a foundation of the movement against militarization. Groups like I Nasion Chamoru, Guahan Coalition for Peace and Justice, Tao’tao’mona Native Rights, and Guahan Indigenous Collective have mobilized different sections of the island community. A new coalition, We Are Guåhan, brought together people from diverse ethnic and occupational backgrounds to advocate for transparency and democratic participation in decisions regarding the future of the island. In California, Famoksaiyan is active in urban centers, particularly among young Chamorros in diaspora.

Because the proposed build-up involves transferring Marines from Okinawa, alliances between Chamorro groups, Okinawan anti-bases activists, and partner organizations in mainland Japan have strengthened opposition to military base expansion in all three places, as organizers stand together in solidarity trying to stop the military from pitting one community against another. Through Pacific-islander networks, Chamorro activists are supported by veteran organizers from Belau, the Marshall Islands, and Hawaii; they are also linked to communities in Latin America and Europe resisting U.S. military expansion through the No US Bases Network.

Chamorro activists are aware of the experiences of long-standing opposition anti-base movements in Okinawa, where opposition over a decade has thus far thwarted US plans to construct a new base at Henoko. Likewise, in South Korea, village residents and supporters waged a 3-year struggle from 2004-2007 to stop the U.S. military taking productive farmland for base expansion in the Pyongtaek area south of Seoul, and current opposition centers on a proposed new Navy base on Jeju Island south of the Korean peninsula.

Okinawan opposition to U.S. bases goes back to 1945, with support from disaffected U.S. troops, particularly African Americans, in the 1970s, and leadership provided by an anti-base governor and Japanese and Okinawan activists during the 1990s. Thousands of Okinawans have worked on U.S. bases as civilians; some receive rent for military use of their land from the Japanese government. Dispossessed Okinawan landowners have been among the participants in the anti-base movement. One significant difference between Okinawa and Guam is the fact that, despite the huge bases located in Okinawa, the U.S.-military economy is now estimated to account for less than 10% of the Okinawan economy, even including indirect income. Like Guam, Okinawa was decimated during World War II; people were dislocated and much of the most fertile land was appropriated for U.S. bases before they were allowed to rebuild their villages. By contrast, Guam has been under colonial rule for centuries. The population is much smaller than Okinawa, and two-thirds of Guam’s residents are outsiders, many of whom are attached to the military. In addition, islanders’ U.S. patriotism runs deep with wartime experiences as recent as World War II and the “liberation” of the island from Japan by U.S. forces. Guam is heavily dependent on the military, which shapes the local economy, patterns of land-use, political priorities, and perhaps most dangerously, the psyches of the people.

The military is adept at playing off one community against another as it seeks to control land and resources to support its over-riding mission: readiness and global domination. After the Philippine Senate withdrew permission for the U.S. Navy to use Subic Bay Naval Base, nuclear submarines started docking at White Beach, Okinawa. Now concerted Okinawan opposition to U.S. bases, specifically the Marines base at Futenma and plans to build a new base at Henoko is being used by the military to put pressure on other locations in the region, notably Guam and Tinian, a small Mariana Island that is politically a part of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Two-thirds of Tinian is currently leased by the U.S. military as part of the CNMI commonwealth negotiations. While members of the Japanese Social Democratic Party have suggested Tinian as an alternative for the Futenma relocation, some islanders have begun to organize a resistance movement. Most recently, the Republic of Belau (Palau) Senate has asked its President to offer its island of Angaur as an alternative location for the Marines base at Futenma.

The struggle against increased militarization on Guam and the Marianas is at a critical stage. After the marathon effort to respond to the DEIS, local organizers are working to keep up with the fast pace of political developments taking place in Washington, balancing the urgency of the hour with longer-term concerns. Given the difficult of getting mainstream media coverage in the continental U.S., the PBS release of Vanessa Warheit’s documentary, The Insular Empire, screened on the island and in selected U.S. cities in March and April 2010, was well timed. There is an urgent need for public education and solidarity actions in the Asia Pacific region and continental United States to increase pressure on the Japanese and U.S. governments regarding the proposed build-up. In January 2010, residents of Okinawa’s Nago City elected a mayor who opposes the construction of the new Marines base in nearby Henoko. The Washington Post quoted Lt. Gen. Keith J. Stalder, commander of U.S. Marine forces in the Pacific as saying, “National security policy cannot be made in towns and villages”.33 In Okinawa and Guam, the question is whether military objectives trump democracy. As Richard P. Lawless told the Asahi Shimbun, “there is no plan B on Henoko”.34 On May 4, under relentless U.S. pressure, Prime Minister Hatoyama visited Okinawa to announce that he would bow to U.S. demands to proceed with the construction of the base at Henoko. The Okinawan population, however, has never been more united in its opposition to construction of a new base on the island.

Commenting on the fact that President Obama is expected to leave the military enclave of Andersen Air Force Base to meet Guam’s leaders and officials during his June visit, Judith Won Pat, Speaker of the Guam Legislature, said that, “the Obama visit appears to be a ‘game-changing’ move to gain local support”.35 The President should take this opportunity to hear people’s deep concerns about the impact of so many additional people on their already weak and overburdened infrastructure, fragile ecosystem, and island culture. He should listen to respected historians like Hope Cristobal, a former Guam senator, and to women leaders, professors, and state representatives active in Fuetsan Famalao’an, who have come together out of concern over the military buildup. He should visit the Hurao Cultural Camp that teaches young children Chamorro language and culture. He should hear the Chamorro people’s deep love for their land, seeking to honor their ancestors and provide for their children. Above all, he should rethink the expansion of U.S. bases in Okinawa, Guam and South Korea. A small fraction of the 2011 federal budget, proposed at $3.8 trillion and including $708 billion for the Department of Defense, could provide residents of Guam with needed medical and educational facilities and improved infrastructure. It could clean-up contaminated water, underwrite job-training programs, and provide for projects that emphasize economic, environmental and cultural sustainability and security. This is a vision for One Guam that leaders in Washington and Guam should consider and support.

LisaLinda Natividad, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor with the Division of Social Work at the University of Guam. She is also President of the Guahan Coalition for Peace and Justice.

Gwyn Kirk, Ph.D. is visiting faculty in Women’s and Gender Studies at University of Oregon (2009-10) and a founder member of Women for Genuine Security (www.genuinesecurity.org).

Recommended citation: LisaLinda Natividad and Gwyn Kirk, “Fortress Guam: Resistance to US Military Mega-Buildup,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 19-1-10, May 10, 2010.

Further Resources

Link 1

Link 2

Maga’haga: Guam Women Leaders Say No to the Military Build-up (Part 1 of 2) on youtube.com.

Vanessa Warheit, The Insular Empire (Horse Opera Productions, 2009)—screened on PBS. Link.

Notes

1 Accessed here.

2 Kerrigan, Kevin. www.pacificnewscenter.com, March 16, 2010.

3 We Are Guåhan press release, March 11, 2010.

4 McCormack, Gavan. 2010. The Travails of a Client State: An Okinawan Angle on the 50th Anniversary of the US-Japan Security Treaty, The Asia-Pacific Journal.

5 Kato, Yoichi. 2010. U.S. Official: Japan Could Lose Entire Marine Presence If Henoko Plan Scrapped. Asahi Shimbun. 3/5/10 online here.

6 Accessed here.

7 Department of Chamorro Affairs, 2008. I Hinanao-ta: A pictorial journey through time. p. 24.

8 Personal communication, Hope Cristobal, historian and former Guam Senator, Sept. 2009.

9 Department of Chamorro Affairs 2008.

10 Accessed here.

11 Palomo, Tony. “Island in Agony: The War in Guam,” in Geoffrey M. White, ed., Remembering the Pacific War. Occasional Paper 36, Center for Pacific Island Studies, School of Hawaiian, Asian & Pacific Studies, University of Hawai’i at Manoa, 1991,133-44.

12 Department of Chamorro Affairs 2008, 25

13 Department of Chamorro Affairs 2008, 25, 34

14 Accessed here.

15 op. cit.

16 Bohane, B., America’s Pacific Speartip, The Diplomat, Sept/Oct. 2007.

17 Assistant Secretary of the Navy, B. J. Penn quoted in Bohane, B., America’s Pacific Speartip, The Diplomat, Sept/Oct 2007, 25.

18 Brooke, James. Guam: What the Pentagon Forgets it Already Has, New York Times, April 7, 2004.

19 op cit

20 Accessed here.

21 Accessed here.

22 Accessed here.

23 Haddock, R. L., & Naval, C. L., 1997. Cancer in Guam: A review of death certificates from 1971-1995. Pacific Health Dialogue, 4(1), 66-75. p. 74.

24 Guam Cancer Facts and Figures 2003-2007, published by the Department of Public Health and Social Services Guam Comprehensive Cancer Control Coalition (October 2009).

25 de Brum, Tony. BRAVO and Today: US Nuclear Tests in the Marshall Islands The Asia-Pacific Journal May 19, 2005

26 EPA/Record of Decision /R09-04/002 2004, 1-1. Accessed here.

27 Tamondong, Dionesis. 2010. “Bordallo Addresses Buildup,” Pacific Daily News, February 17, 2010. Accessed here.

28 op cit

29 Accessed here.

30 op cit

31 Accessed here.

32 Weaver, Teri. 2010. EPA analysis finds military’s plan for Guam growth is ‘inadequate,’ Stars and Stripes, Pacific edition. Saturday February 27. Accessed here.

33 Harden, Blaine. 2010. Mayor’s election in Okinawa is setback for U.S. air base move, Washington Post 1/25/10. Accessed here.

34 Kato 2010.

35 Cited by Jeff Marchesseault, February 1, 2010, from this source.