http://www.tomdispatch.com/post/175214/tomgram:_john_feffer,_can_japan_say_no_to_washington/

Tomgram: John Feffer, Can Japan Say No to Washington?

Posted by John Feffer at 11:15am, March 4, 2010.

When it comes to cracks in America’s imperial edifice — as measured by the ability of other countries to say “no” to Washington, or just look the other way when American officials insist on something — Europe has been garnering all the headlines lately, and they’ve been wildly American-centric. “Gates: Nato, in crisis, must change its ways,” “Pull Your Weight, Europe,” “Gates: Europe’s demilitarization has gone too far,” “Dutch Retreat,” and so on. All this over one country — Holland — which will evidently pull out of Afghanistan thanks to intensifying public pressure about the war there, and other NATO countries whose officials are shuffling their feet and hemming and hawing about sending significant reinforcements Afghanistan-wards. One could, of course, imagine quite a different set of headlines (“Europeans react to overbearing, overmuscled Americans,” “Europeans turn backs on endless war”), but not in the mainstream news. You can certainly find some striking commentary on the subject by figures like Andrew Bacevich and Juan Cole, but it goes unheeded.

The truth is that Europe still seems a long way from being ready to offer any set of firm noes to Washington on much of anything, while in Asia, noes from key American clients of the past half-century have been even less in evidence. But sometimes from the smallest crack in a façade come the largest of changes. In this case, the most modest potential “no” from a new Japanese government in Tokyo, concerning U.S. basing posture in that country, seems to have caused near panic in Washington. In neither Europe nor Asia have we felt any political earthquakes — yet. But just below the surface, the global political tectonic plates are rubbing together, and who knows when, as power on this planet slowly shifts, one of them will slip and suddenly, for better or worse, the whole landscape of power will look different.

John Feffer, the co-director of Foreign Policy in Focus and a TomDispatch regular, already has written for this site on whether Afghanistan might prove NATO’s graveyard. Now, he turns east to explore whether, in a dispute over one insignificant base on the Japanese island of Okinawa, we might be feeling early rumblings on the Asian fault-line of American global power. Tom

Pacific Pushback

Has the U.S. Empire of Bases Reached Its High-Water Mark?

By John Feffer

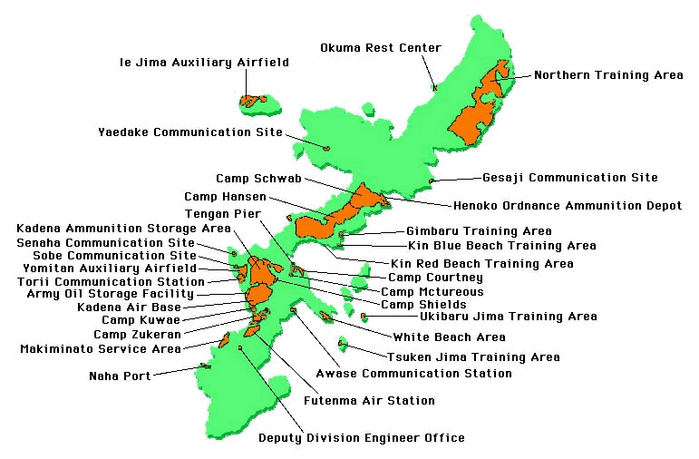

For a country with a pacifist constitution, Japan is bristling with weaponry. Indeed, that Asian land has long functioned as a huge aircraft carrier and naval base for U.S. military power. We couldn’t have fought the Korean and Vietnam Wars without the nearly 90 military bases scattered around the islands of our major Pacific ally. Even today, Japan remains the anchor of what’s left of America’s Cold War containment policy when it comes to China and North Korea. From the Yokota and Kadena air bases, the United States can dispatch troops and bombers across Asia, while the Yokosuka base near Tokyo is the largest American naval installation outside the United States.

You’d think that, with so many Japanese bases, the United States wouldn’t make a big fuss about closing one of them. Think again. The current battle over the Marine Corps air base at Futenma on Okinawa — an island prefecture almost 1,000 miles south of Tokyo that hosts about three dozen U.S. bases and 75% of American forces in Japan — is just revving up. In fact, Washington seems ready to stake its reputation and its relationship with a new Japanese government on the fate of that base alone, which reveals much about U.S. anxieties in the age of Obama.

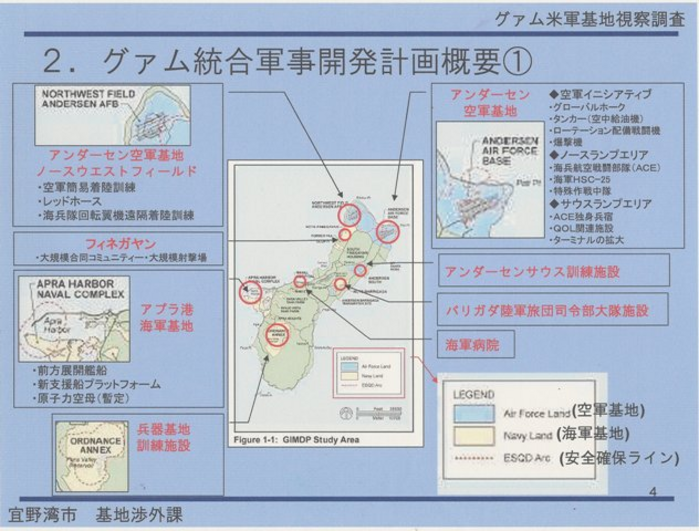

What makes this so strange, on the surface, is that Futenma is an obsolete base. Under an agreement the Bush administration reached with the previous Japanese government, the U.S. was already planning to move most of the Marines now at Futenma to the island of Guam. Nonetheless, the Obama administration is insisting, over the protests of Okinawans and the objections of Tokyo, on completing that agreement by building a new partial replacement base in a less heavily populated part of Okinawa.

The current row between Tokyo and Washington is no mere “Pacific squall,” as Newsweek dismissively described it. After six decades of saying yes to everything the United States has demanded, Japan finally seems on the verge of saying no to something that matters greatly to Washington, and the relationship that Dwight D. Eisenhower once called an “indestructible alliance” is displaying ever more hairline fractures. Worse yet, from the Pentagon’s perspective, Japan’s resistance might prove infectious — one major reason why the United States is putting its alliance on the line over the closing of a single antiquated military base and the building of another of dubious strategic value.

During the Cold War, the Pentagon worried that countries would fall like dominoes before a relentless Communist advance. Today, the Pentagon worries about a different kind of domino effect. In Europe, NATO countries are refusing to throw their full support behind the U.S. war in Afghanistan. In Africa, no country has stepped forward to host the headquarters of the Pentagon’s new Africa Command. In Latin America, little Ecuador has kicked the U.S. out of its air base in Manta.

All of these are undoubtedly symptoms of the decline in respect for American power that the U.S. military is experiencing globally. But the current pushback in Japan is the surest sign yet that the American empire of overseas military bases has reached its high-water mark and will soon recede.

Toady No More?

Until recently, Japan was virtually a one-party state, and that suited Washington just fine. The long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) had the coziest of bipartisan relations with that city’s policymakers and its “chrysanthemum club” of Japan-friendly pundits. A recent revelation that, in 1969, Japan buckled to President Richard Nixon’s demand that it secretly host U.S. ships carrying nuclear weapons — despite Tokyo’s supposedly firm anti-nuclear principles — has pulled back the curtain on only the tip of the toadyism.

During and after the Cold War, Japanese governments bent over backwards to give Washington whatever it wanted. When government restrictions on military exports got in the way of the alliance, Tokyo simply made an exception for the United States. When cooperation on missile defense contradicted Japan’s ban on militarizing space, Tokyo again waved a magic wand and made the restriction disappear.

Although Japan’s constitution renounces the “threat or the use of force as a means of settling international disputes,” Washington pushed Tokyo to offset the costs of the U.S. military adventure in the first Gulf War against Saddam Hussein in 1990-1991, and Tokyo did so. Then, from November 2001 until just recently, Washington persuaded the Japanese to provide refueling in the Indian Ocean for vessels and aircraft involved in the war in Afghanistan. In 2007, the Pentagon even tried to arm-twist Tokyo into raising its defense spending to pay for more of the costs of the alliance.

Of course, the LDP complied with such demands because they intersected so nicely with its own plans to bend that country’s peace constitution and beef up its military. Over the last two decades, in fact, Japan has acquired remarkably sophisticated hardware, including fighter jets, in-air refueling capability, and assault ships that can function like aircraft carriers. It also amended the 1954 Self-Defense Forces Law, which defines what the Japanese military can and cannot do, more than 50 times to give its forces the capacity to act with striking offensive strength. Despite its “peace constitution,” Japan now has one of the top militaries in the world.

Enter the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ). In August 2009, that upstart political party dethroned the LDP, after more than a half-century in power, and swept into office with a broad mandate to shake things up. Given the country’s nose-diving economy, the party’s focus has been on domestic issues and cost-cutting. Not surprisingly, however, the quest to cut pork from the Japanese budget has led the party to scrutinize the alliance with the U.S. Unlike most other countries that host U.S. military bases, Japan shoulders most of the cost of maintaining them: more than $4 billion per year in direct or indirect support.

Under the circumstances, the new government of Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama proposed something modest indeed — putting the U.S.-Japan alliance on, in the phrase of the moment, a “more equal” footing. It inaugurated this new approach in a largely symbolic way by ending Japan’s resupply mission in the Indian Ocean (though Tokyo typically sweetened the pill by offering a five-year package of $5 billion in development assistance to the Afghan government).

More substantively, the Hatoyama government also signaled that it wanted to reduce its base-support payments. Japan’s proposed belt-tightening comes at an inopportune moment for the Obama administration, as it tries to pay for two wars, its “overseas contingency operations,” and a worldwide network of more than 700 military bases. The burdens of U.S. overseas operations are increasing, and fewer countries are proving willing to share the costs.

Of Dugongs and Democracy

The immediate source of tension in the U.S.-Japanese relationship has been Tokyo’s desire to renegotiate that 2006 agreement to close Futenma, transfer those 8,000 Marines to Guam, and build a new base in Nago, a less densely populated area of the island. It’s a deal that threatens to make an already strapped government pay big. Back in 2006, Tokyo promised to shell out more than $6 billion just to help relocate the Marines to Guam.

The political cost to the new government of going along with the LDP’s folly may be even higher. After all, the DPJ received a healthy chunk of voter support from Okinawans, dissatisfied with the 2006 agreement and eager to see the American occupation of their island end. Over the last several decades, with U.S. bases built cheek-by-jowl in the most heavily populated parts of the island, Okinawans have endured air, water, and noise pollution, accidents like a 2004 U.S. helicopter crash at Okinawa International University, and crimes that range from trivial speeding violations all the way up to the rape of a 12-year-old girl by three Marines in 1995. According to a June 2009 opinion poll, 68% of Okinawans opposed relocating Futenma within the prefecture, while only 18% favored the plan. Meanwhile, the Social Democratic Party, a junior member of the ruling coalition, has threatened to pull out if Hatoyama backs away from his campaign pledge not to build a new base in Okinawa.

Then there’s the dugong, a sea mammal similar to the manatee that looks like a cross between a walrus and a dolphin and was the likely inspiration for the mermaid myth. Only 50 specimens of this endangered species are still living in the marine waters threatened by the proposed new base near less populated Nago. In a landmark case, Japanese lawyers and American environmentalists filed suit in U.S. federal court to block the base’s construction and save the dugong. Realistically speaking, even if the Pentagon were willing to appeal the case all the way up to the Supreme Court, lawyers and environmentalists could wrap the U.S. military in so much legal and bureaucratic red tape for so long that the new base might never leave the drawing board.

For environmental, political, and economic reasons, ditching the 2006 agreement is a no-brainer for Tokyo. Given Washington’s insistence on retaining a base of little strategic importance, however, the challenge for the DPJ has been to find a site other than Nago. The Japanese government floated the idea of merging the Futenma facility with existing facilities at Kadena, another U.S. base on the island. But that plan — as well as possible relocation to other parts of Japan — has met with stiff local resistance. A proposal to further expand facilities in Guam was nixed by the governor there.

The solution to all this is obvious: close down Futenma without opening another base. But so far, the United States is refusing to make it easy for the Japanese. In fact, Washington is doing all it can to box the new government in Tokyo into a corner.

Ratcheting Up the Pressure

The U.S. military presence in Okinawa is a residue of the Cold War and a U.S. commitment to containing the only military power on the horizon that could threaten American military supremacy. Back in the 1990s, the Clinton administration’s solution to a rising China was to “integrate, but hedge.” The hedge — against the possibility of China developing a serious mean streak — centered around a strengthened U.S.-Japan alliance and a credible Japanese military deterrent.

What the Clinton administration and its successors didn’t anticipate was how effectively and peacefully China would disarm this hedging strategy with careful statesmanship and a vigorous trade policy. A number of Southeast Asian countries, including the Philippines and Indonesia, succumbed early to China’s version of checkbook diplomacy. Then, in the last decade, South Korea, like the Japanese today, started to talk about establishing “more equal” relations with the United States in an effort to avoid being drawn into any future military scrape between Washington and Beijing.

Now, with its arch-conservatives gone from government, Japan is visibly warming to China’s charms. In 2007, China had already surpassed the United States as the country’s leading trade partner. On becoming prime minister, Hatoyama sensibly proposed the future establishment of an East Asian community patterned on the European Union. As he saw it, that would leverage Japan’s position between a rising China and a United States in decline. In December, while Washington and Tokyo were haggling bitterly over the Okinawa base issue, DPJ leader Ichiro Ozawa sent a signal to Washington as well as Beijing by shepherding a 143-member delegation of his party’s legislators on a four-day trip to China.

Not surprisingly, China’s bedazzlement policy has set off warning bells in Washington, where the People’s Republic is still a focus of primary concern for a cadre of strategic planners inside the Pentagon. The Futenma base — and its potential replacement — would be well situated, should Washington ever decide to send rapid response units to the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea, or the Korean peninsula. Strategic planners in Washington like to speak of the “tyranny of distance,” of the difficulty of getting “boots on the ground” from Guam or Hawaii in case of an East Asian emergency.

Yet the actual strategic value of Futenma is, at best, questionable. The South Koreans are more than capable of dealing with any contingency on the peninsula. And the United States frankly has plenty of firepower by air (Kadena) and sea (Yokosuka) within hailing distance of China. A couple thousand Marines won’t make much of a difference (though the leathernecks strenuously disagree). However, in a political environment in which the Pentagon is finding itself making tough choices between funding counterinsurgency wars and old Cold War weapons systems, the “China threat” lobby doesn’t want to give an inch. Failure to relocate the Futenma base within Okinawa might be the first step down a slippery slope that could potentially put at risk billions of dollars in Cold War weapons still in the production line. It’s hard to justify buying all the fancy toys without a place to play with them.

And that’s one reason the Obama administration has gone to the mat to pressure Tokyo to adhere to the 2006 agreement. It even dispatched Secretary of Defense Robert Gates to the Japanese capital last October in advance of President Obama’s own Asian tour. Like an impatient father admonishing an obstreperous teenager, Gates lectured the Japanese “to move on” and abide by the agreement — to the irritation of both the new government and the public.

The punditocracy has predictably closed ranks behind a bipartisan Washington consensus that the new Japanese government should become as accustomed to its junior status as its predecessor and stop making a fuss. The Obama administration is frustrated with “Hatoyama’s amateurish handling of the issue,” writes Washington Post editorial page editor Fred Hiatt. “What has resulted from Mr. Hatoyama’s failure to enunciate a clear strategy or action plan is the biggest political vacuum in over 50 years,” adds Victor Cha, former director of Asian affairs at the National Security Council. Neither analyst acknowledges that Tokyo’s only “failure” or “amateurish” move was to stand up to Washington. “The dispute could undermine security in East Asia on the 50th anniversary of an alliance that has served the region well,” intoned The Economist more bluntly. “Tough as it is for Japan’s new government, it needs to do most, though not all, of the caving in.”

The Hatoyama government is by no means radical, nor is it anti-American. It isn’t preparing to demand that all, or even many, U.S. bases close. It isn’t even preparing to close any of the other three dozen (or so) bases on Okinawa. Its modest pushback is confined to Futenma, where it finds itself between the rock of Japanese public opinion and the hard place of Pentagon pressure.

Those who prefer to achieve Washington’s objectives with Japan in a more roundabout fashion counsel patience. “If America undercuts the new Japanese government and creates resentment among the Japanese public, then a victory on Futenma could prove Pyrrhic,” writes Joseph Nye, the architect of U.S. Asia policy during the Clinton years. Japan hands are urging the United States to wait until the summer, when the DPJ has a shot at picking up enough additional seats in the next parliamentary elections to jettison its coalition partners, if it deems such a move necessary.

Even if the Social Democratic Party is no longer in the government constantly raising the Okinawa base issue, the DPJ still must deal with democracy on the ground. The Okinawans are dead set against a new base. The residents of Nago, where that base would be built, just elected a mayor who campaigned on a no-base platform. It won’t look good for the party that has finally brought real democracy to Tokyo to squelch it in Okinawa.

Reverse Island Hop

Wherever the U.S. military puts down its foot overseas, movements have sprung up to protest the military, social, and environmental consequences of its military bases. This anti-base movement has notched some successes, such as the shut-down of a U.S. navy facility in Vieques, Puerto Rico, in 2003. In the Pacific, too, the movement has made its mark. On the heels of the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo, democracy activists in the Philippines successfully closed down the ash-covered Clark Air Force Base and Subic Bay Naval Station in 1991-1992. Later, South Korean activists managed to win closure of the huge Yongsan facility in downtown Seoul.

Of course, these were only partial victories. Washington subsequently negotiated a Visiting Forces Agreement with the Philippines, whereby the U.S. military has redeployed troops and equipment to the island, and replaced Korea’s Yongsan base with a new one in nearby Pyeongtaek. But these not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) victories were significant enough to help edge the Pentagon toward the adoption of a military doctrine that emphasizes mobility over position. The U.S. military now relies on “strategic flexibility” and “rapid response” both to counter unexpected threats and to deal with allied fickleness.

The Hatoyama government may indeed learn to say no to Washington over the Okinawa bases. Evidently considering this a likelihood, former deputy secretary of state and former U.S. ambassador to Japan Richard Armitage has said that the United States “had better have a plan B.” But the victory for the anti-base movement will still be only partial. U.S. forces will remain in Japan, and especially Okinawa, and Tokyo will undoubtedly continue to pay for their maintenance.

Buoyed by even this partial victory, however, NIMBY movements are likely to grow in Japan and across the region, focusing on other Okinawa bases, bases on the Japanese mainland, and elsewhere in the Pacific, including Guam. Indeed, protests are already building in Guam against the projected expansion of Andersen Air Force Base and Naval Base Guam to accommodate those Marines from Okinawa. And this strikes terror in the hearts of Pentagon planners.

In World War II, the United States employed an island-hopping strategy to move ever closer to the Japanese mainland. Okinawa was the last island and last major battle of that campaign, and more people died during the fighting there than in the subsequent atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined: 12,000 U.S. troops, more than 100,000 Japanese soldiers, and perhaps 100,000 Okinawan civilians. This historical experience has stiffened the pacifist resolve of Okinawans.

The current battle over Okinawa again pits the United States against Japan, again with the Okinawans as victims. But there is a good chance that the Okinawans, like the Na’vi in that great NIMBY film Avatar, will win this time.

A victory in closing Futenma and preventing the construction of a new base might be the first step in a potential reverse island hop. NIMBY movements may someday finally push the U.S. military out of Japan and off Okinawa. It’s not likely to be a smooth process, nor is it likely to happen any time soon. But the kanji is on the wall. Even if the Yankees don’t know what the Japanese characters mean, they can at least tell in which direction the exit arrow is pointing.

John Feffer is the co-director of Foreign Policy in Focus at the Institute for Policy Studies and writes its regular World Beat column. His past essays, including those for TomDispatch.com, can be read at his website. For more information on the growing movement against the U.S. base in Okinawa, join the Facebook group I Oppose the Expansion of US Bases in Okinawa

Copyright 2010 John Feffer