From the online journal Japan Focus, an excellent article by Catherine Lutz, the editor of the book Bases of Empire.

Catherine Lutz

Much about our current world is unparalleled: holes in the ozone layer, the commercial patenting of life forms, degrading poverty on a massive scale, and, more hopefully, the rise of concepts of global citizenship and universal human rights. Less visible but equally unprecedented is the global omnipresence and unparalleled lethality of the U.S. military, and the ambition with which it is being deployed around the world. These bases bristle with an inventory of weapons whose worth is measured in the trillions and whose killing power could wipe out all life on earth several times over. Their presence is meant to signal, and at times demonstrate, that the US is able and willing to attempt to control events in other regions militarily. The start of a new administration in Washington, and the possibility that world economic depression will give rise to new tensions and challenges, provides an important occasion to review the global structures of American power.

Officially, over 190,000 troops and 115,000 civilian employees are massed in 909 military facilities in 46 countries and territories.[1] There, the US military owns or rents 795,000 acres of land, and 26,000 buildings and structures valued at $146 billion. These official numbers are quite misleading as to the scale of US overseas military basing, however, excluding as they do the massive buildup of new bases and troop presence in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as secret or unacknowledged facilities in Israel, Kuwait, the Philippines and many other places. $2 billion in military construction money has been expended in only three years of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Just one facility in Iraq, Balad Air Base, houses 30,000 troops and 10,000 contractors, and extends across 16 square miles with an additional 12 square mile “security perimeter.”

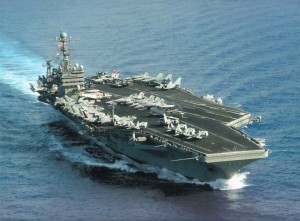

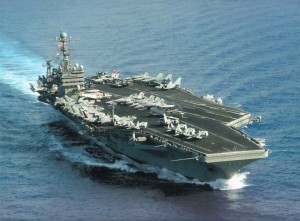

Deployed from those battle zones in Afghanistan and Iraq to the quiet corners of Curacao, Korea, and England, the US military domain consists of sprawling Army bases, small listening posts, missile and artillery testing ranges, and berthed aircraft carriers.[2] While the bases are literally barracks and weapons depots and staging areas for war making and ship repair facilities and golf courses and basketball courts, they are also political claims, spoils of war, arms sales showrooms, toxic industrial sites, laboratories for cultural (mis)communication, and collections of customers for local bars, shops, and prostitution.

The environmental, political, and economic impact of these bases is enormous and, despite Pentagon claims that the bases simply provide security to the regions they are in, most of the world’s people feel anything but reassured by this global reach. Some communities pay the highest price: their farm land taken for bases, their children neurologically damaged by military jet fuel in their water supply, their neighbors imprisoned, tortured and disappeared by the autocratic regimes that survive on US military and political support given as a form of tacit rent for the bases. Global opposition to U.S. basing has been widespread and growing, however, and this essay provides an overview of both the worldwide network of U.S. military bases and the vigorous campaigns to hold the U.S. accountable for that damage and to reorient their countries’ security policies in other, more human, and truly secure directions.

Military bases are “installations routinely used by military forces” (Blaker 1990:4). They represent a confluence of labor (soldiers, paramilitary workers, and civilians), land, and capital in the form of static facilities, supplies, and equipment. They should also include the eleven US aircraft carriers, often used to signal the possibility of US bombing and invasion as they are brought to “trouble spots” around the world. They were, for example, the primary base of US airpower during the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The US Navy refers to each carrier as “four and a half acres of sovereign US territory.” These moveable bases and their land-based counterparts are just the most visible part of the larger picture of US military presence overseas. This picture of military access includes (1) US military training of foreign forces, often in conjunction with the provision of US weaponry, (2) joint exercises meant to enhance US soldiers’ exposure to a variety of operating environments from jungle to desert to urban terrain and interoperability across national militaries, and (3) legal arrangements made to gain overflight rights and other forms of ad hoc use of others’ territory as well as to preposition military equipment there. In all of these realms, the US is in a class by itself, no adversary or ally maintaining anything comparable in terms of its scope, depth and global reach.

US forces train 100,000 soldiers annually in 180 countries, the presumption being that beefed-up local militaries will help pursue U.S. interests in local conflicts and save the U.S. money, casualties, and bad publicity when human rights abuses occur.[3] Moreover, working with other militaries is important, strategists say, because “these low-tech militaries may well be U.S. partners or adversaries in future contingencies, [necessitating] becoming familiar with their capabilities and operating style and learning to operate with them” (Cliff & Shapiro 2003:102). The blowback effects are especially well known since September 11 (Johnson 2000). Less well known is that these training programs strengthen the power of military forces in relation to other sectors within those countries, sometimes with fragile democracies, and they may include explicit training in assassination and torture techniques. Fully 38 percent of those countries with US basing were cited in 2002 for their poor human rights record (Lumpe 2002:16).

The US military presence also involves jungle, urban, desert, maritime, and polar training exercises across wide swathes of landscape. These exercises have sometimes been provocative to other nations, and in some cases have become the pretext for substantial and permanent positioning of troops; in recent years, for example, the US has run approximately 20 exercises annually on Philippine soil. This has meant a near continuous presence of US troops in a country whose people ejected US bases in 1992 and continue to vigorously object to their reinsertion, and whose Constitution forbids the basing of foreign troops. In addition, these exercises ramp up even more than usual the number and social and environmental impact of daily jet landings and sailors on liberty around US bases (Lindsay Poland 2003).

Finally, US military and civilian personnel work to shape local legal codes to facilitate US access. They have lobbied, for example, to change the Philippine and Japanese constitutions to allow, respectively, foreign troop basing, US nuclear weapons, and a more-than-defensive military in the service of US wars, in the case of Japan. “Military diplomacy” with local civil and military elites is conducted not only to influence such legislation but also to shape opinion in what are delicately called “host” countries. US military and civilian officials are joined in their efforts by intelligence agents passing as businessmen or diplomats; in 2005, the US Ambassador to the Philippines created a furor by mentioning that the US has 70 agents operating in Mindanao alone.

Much of U.S. weaponry, nuclear and otherwise, is stored at places like Camp Darby in Italy, Kadena Air Force Base in Okinawa, and the Naval Magazine on Guam, as well as in nuclear submarines and on the Navy’s other floating bases.[4] The weapons, personnel, and fossil fuels involved in this US military presence cost billions of dollars, most coming from US taxpayers but an increasing number of billions from the citizens of the countries involved, particularly Japan. Elaborate bilateral negotiations exchange weapons, cash, and trade privileges for overflight and land use rights. Less explicitly, but no less importantly, rice import levels or immigration rights to the US or overlooking human rights abuses have been the currency of exchange, for example in enlisting mercenaries from the islands of Oceania (Cooley 2008).

Bases are the literal and symbolic anchors, and the most visible centerpieces, of the U.S. military presence overseas. To understand where those bases are and how they are being used is essential for understanding the United States’ relationship with the rest of the world, the role of coercion in it, and its political economic complexion. I ask why this empire of bases was established in the first place, how the bases are currently configured around the world and how that configuration is changing.

What Are Bases For?

Foreign military bases have been established throughout the history of expanding states and warfare. They proliferate where a state has imperial ambitions, either through direct control of territory or through indirect control over the political economy, laws, and foreign policy of other places. Whether or not it recognizes itself as such, a country can be called an empire when it projects substantial power with the aim of asserting and maintaining dominance over other regions. Those policies succeed when wealth is extracted from peripheral areas, and redistributed to the imperial center. Empires, then, have historically been associated with a growing gap between the wealth and welfare of the powerful center and the regions it dominates. Alongside and supporting these goals has often been elevated self-regard in the imperial power, or a sense of racial, cultural, or social superiority.

The descriptors empire and imperialism have been applied to the Romans, Incas, Mongols, Persians, Portuguese, Spanish, Ottomans, Dutch, British, Soviet Union, China, Japan, and the United States, among others. Despite the striking differences between each of these cases, each used military bases to maintain some forms of rule over regions far from their center. The bases eroded the sovereignty of allied states on which they were established by treaty; the Roman Empire was accomplished not only by conquest, but also “by taking her weaker [but still sovereign] neighbors under her wing and protecting them against her and their stronger neighbors… The most that Rome asked of them in terms of territory was the cessation, here and there, of a patch of ground for the plantation of a Roman fortress” (Magdoff et al. 2002).

What have military bases accomplished for these empires through history? Bases are usually presented, above all, as having rational, strategic purposes; the empire claims that they provide forward defense for the homeland, supply other nations with security, and facilitate the control of trade routes and resources. They have been used to protect non-economic actors and their agendas as well – missionaries, political operatives, and aid workers among them. In the 16th century, the Portuguese, for example, seized profitable ports along the route to India and used demonstration bombardment, fortification, and naval patrols to institute a semi-monopoly in the spice trade. They militarily coerced safe passage payments and duties from local traders via key fortified ports. More recently as well, bases have been used to control the political and economic life of the host nation: US bases in Korea, for example, have been key parts of the continuing control that the US military exercises over Korean forces, and Korean foreign policy more generally, extracting important political and military support, for example, for its wars in Vietnam and Iraq. Politically, bases serve to encourage other governments’ endorsement of US military and other foreign policy. Moreover, bases have not simply been planned in keeping with strategic and political goals, but are the result of institutionalized bureaucratic and political economic imperatives, that is, corporations and the military itself as an organization have a powerful stake in bases’ continued existence regardless of their strategic value (Johnson 2004).

Alongside their military and economic functions, bases have symbolic and psychological dimensions. They are highly visible expressions of a nation’s will to status and power. Strategic elites have built bases as a visible sign of the nation’s standing, much as they have constructed monuments and battleships. So, too, contemporary US politicians and the public have treated the number of their bases as indicators of the nation’s hyperstatus and hyperpower. More darkly, overseas military bases can also be seen as symptoms of irrational or untethered fears, even paranoia, as they are built with the long-term goal of taming a world perceived to be out of control. Empires frequently misperceive the world as rife with threats and themselves as objects of violent hostility from others. Militaries’ interest in organizational survival has also contributed to the amplification of this fear and imperial basing structures as the solution as they “sell themselves” to their populace by exaggerating threats, underestimating the costs of basing and war itself, as well as understating the obstacles facing preemption and belligerence (Van Evera 2001).

As the world economy and its technological substructures have changed, so have the roles of foreign bases. By 1500, new sailing technologies allowed much longer distance voyages, even circumnavigational ones, and so empires could aspire to long networks of coastal naval bases to facilitate the control of sea lanes and trade. They were established at distances that would allow provisioning the ship, taking on fresh fruit that would protect sailors from scurvy, and so on. By the 21st century, technological advances have at least theoretically eliminated many of the reasons for foreign bases, given the possibilities of in transit refueling of jets and aircraft carriers, the nuclear powering of submarines and battleships, and other advances in sea and airlift of military personnel and equipment. Bases have, nevertheless, continued their ineluctable expansion.

US Aircraft Carrier in the Persian Gulf

States that invest their people’s wealth in overseas bases have paid direct as well as opportunity costs, whose consequences in the long run have usually been collapse of the empire. In The Rise and Fall of Great Powers, Kennedy notes that previous empires which established and tenaciously held onto overseas bases inevitably saw their wealth and power decay. He finds that history

. . . demonstrates that military ‘security’ alone is never enough. It may, over the shorter term, deter or defeat rival states….[b]ut if, by such victories, the nation over-extends itself geographically and strategically; if, even at a less imperial level, it chooses to devote a large proportion of its total income to ‘protection,’ leaving less for ‘productive investment,’ it is likely to find its economic output slowing down, with dire implications for its long-term capacity to maintain both its citizens’ consumption demands and its international position (Kennedy 1987:539).[5]

Nonetheless, U.S. defense officials and scholars have continued to argue that bases lead to “enhanced national security and successful foreign policy” because they provide “a credible capacity to move, employ, and sustain military forces abroad,” (Blaker 1990:3) and the ability “to impose the will of the United States and its coalition partners on any adversaries.”[6] This belief helps sustain the US basing structure, which far exceeds any the world has seen: this is so in terms of its global reach, depth, and cost, as well as its impact on geopolitics in all regions of the world, particularly the Asia-Pacific.

A Short History of US Bases

In 1938, the US had 14 military bases outside its continental borders. Seven years and 55 million World War II deaths later (of which a small fraction — 400,000 — were US citizens), the United States had an astounding 30,000 installations large and small in approximately 100 countries. While this number was projected to contract to 2,000 by 1948, the global scale of US military basing would remain a major legacy of the Second World War, and with it, providing the sinews for the rise to global hegemony of the United States (Blaker 1990:22).

After consolidation of continental dominance, there were three periods of expansive global ambition in US history beginning in 1898, 1945, and 2001. Each is associated with the acquisition of significant numbers of new overseas military bases. The Spanish-American war resulted in the acquisition of a number of colonies, many of which have remained under US control in the century since. Nonetheless, by 1920, popular support for international expansion in the US had been diminished by the Russian Revolution, by growing domestic labor militancy, and by a rising nationalism, culminating in the US Senate’s rejection of the League of Nations (Smith 2003). So it was that as late as 1938, the US basing system was far smaller than that of its political and economic peers including many European nations as well as Japan. US soldiers were stationed in just 14 bases, some quite small, in Puerto Rico, Cuba, Panama, the Virgin Islands, Hawaii, Midway, Wake, and Guam, the Philippines, Shanghai, two in the Aleutians, American Samoa, and Johnston Island (Harkavy 1982). This small number was the result in part of a strong anti-statist and anti-militarist strain in US political culture (Sherry 1995). From the perspective of many in the US through the inter-war period, to build bases would be to risk unwarranted entanglement in others’ conflicts. Bases nevertheless positioned the US in both Latin America and the Asia-Pacific.

Many of the most important and strategic international bases of this era were those of rival empires, with by far the largest number belonging to the British Empire. In order of magnitude, the other colonial powers with basing included France, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Italy, Japan, and, only then, the US. Conversely, some countries with large militaries and even some with expansive ambitions had relatively few overseas bases; Germany and the Soviet Union had almost none. But the attempt to acquire such bases would be a contributing cause of World War II (Harkavy 1989:5).

The bulk of the US basing system was established during World War II, beginning with a deal cut with Great Britain for the long-term lease of base facilities in six British colonies in the Caribbean in 1941 in exchange for some decrepit US destroyers. The same year, the US assumed control of formerly Danish bases in Greenland and Iceland (Harkavy 1982:68). The rationale for building bases in the Western Hemisphere was in part to discourage or prevent the Germans from doing so; at the same time, the US did not, before Pearl Harbor, expand or build new bases in the Asia-Pacific on the assumption that they might be indefensible and that they could even provoke Japanese attack.

By the end of the war in 1945, the United States had 30,000 installations spread throughout the world, as already mentioned. The Soviet Union had bases in Eastern Europe, but virtually no others until the 1970s, when they expanded rapidly, especially in Africa and the Indian Ocean area (Harkavy 1982). While Truman was intent on maintaining bases the US had taken or created in the war, many were closed by 1949 (Blaker 1990:30). Pressure came from Australia, France, and England, as well as from Panama, Denmark and Iceland, for return of bases in their own territory or colonies, and domestically to demobilize the twelve million man military (a larger military would have been needed to maintain the vast basing system). More important than the shrinking number of bases, however, was the codification of US military access rights around the world in a comprehensive set of legal documents. These established security alliances with multiple states within Europe (NATO), the Middle East and South Asia (CENTO), and Southeast Asia (SEATO), and they included bilateral arrangements with Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. These alliances assumed a common security interest between the United States and other countries and were the charter for US basing in each place. Status of Forces Agreements (SOFAs) were crafted in each country to specify what the military could do; these usually gave US soldiers broad immunity from prosecution for crimes committed and environmental damage created. These agreements and subsequent base operations have usually been shrouded in secrecy.

In the United States, the National Security Act of 1947, along with a variety of executive orders, instituted what can be called a second, secret government or the “national security state”, which created the National Security Agency, National Security Council, and Central Intelligence Agency and gave the US president expansive new imperial powers. From this point on, domestic and especially foreign military activities and bases were to be heavily masked from public oversight (Lens 1987). Begun as part of the Manhattan Project, the black budget is a source of defense funds secret even to Congress, and one that became permanent with the creation of the CIA. Under the Reagan administration, it came to be relied on more and more for a variety of military and intelligence projects and by one estimate was $36 billion in 1989 (Blaker 1990:101, Weiner 1990:4). Many of those unaccountable funds then and now go into use overseas, flowing out of US embassies and military bases. There they have helped the US to work vigorously to undermine and change local laws that restrict its military plans; it has interfered for years in the domestic affairs of nations in which it has or desires military access, including attempts to influence votes on and change anti-nuclear and anti-war provisions in the Constitutions of the Pacific nation of Belau and of Japan.

The number of US bases was to rise again during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, reaching back to 1947 levels by the year 1967 (Blaker 1990:33). The presumption was established that bases captured or created during wartime would be permanently retained. Certain ideas about basing and what it accomplished were to be retained from World War II as well, including the belief that “its extensive overseas basing system was a legitimate and necessary instrument of U.S. power, morally justified and a rightful symbol of the U.S. role in the world” (Blaker 1990:28).

Nonetheless, over the second half of the 20th century, the United States was either evicted or voluntarily left bases in dozens of countries.[7] Between 1947 and 1990, the US was asked to leave France, Yugoslavia, Iran, Ethiopia, Libya, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Algeria, Vietnam, Indonesia, Peru, Mexico, and Venezuela. Popular and political objection to the bases in Spain, the Philippines, Greece, and Turkey in the 1980s enabled those governments to negotiate significantly more compensation from the United States. Portugal threatened to evict the US from important bases in the Azores, unless it ceased its support for independence for its African colonies, a demand with which the US complied.[8] In the 1990s and later, the US was sent packing, most significantly, from the Philippines, Panama, Saudi Arabia, Vieques, and Uzbekistan (see McCaffery, this volume).

At the same time, US bases were newly built after 1947 in remarkable numbers (241) in the Federal Republic of Germany, as well as in Italy, Britain, and Japan (Blaker 1990:45). The defeated Axis powers continued to host the most significant numbers of US bases: at its height, Japan was peppered with 3,800 US installations.

As battles become bases, so bases become battles; the bases in East Asia acquired in the Spanish American War and in World War II, such as Guam, Okinawa and the Philippines, became the primary sites from which the United States waged war on Vietnam. Without them, the costs and logistical obstacles for the US would have been immense. The number of bombing runs over North and South Vietnam required tons of bombs unloaded, for example, at the Naval Station in Guam, stored at the Naval Magazine in the southern area of the island, and then shipped up to be loaded onto B-52s at Anderson Air Force Base every day during years of the war. The morale of ground troops based in Vietnam, as fragile as it was to become through the latter part of the 1960s, depended on R & R at bases throughout East and Southeast Asia which would allow them to leave the war zone and yet be shipped back quickly and inexpensively for further fighting (Baker 2004:76). In addition to the bases’ role in fighting these large and overt wars, they facilitated the movement of military assets to accomplish the over 200 military interventions the US waged in the Cold War period (Blum 1995).

While speed of deployment is framed as an important continued reason for forward basing, troops could be deployed anywhere in the world from US bases without having to touch down en route. In fact, US soldiers are being increasingly billeted on US territory, including such far-flung areas as Guam, which is presently slated for a larger buildup, for this reason as well as to avoid the political and other costs of foreign deployment.

U.S. military bases on Guam

With the will to gain military control of space, as well as gather intelligence, the US over time, and especially in the 1990s, established a large number of new military bases to facilitate the strategic use of communications and space technologies. Military R&D (the Pentagon spent over $52 billion in 2005 and employed over 90,000 scientists) and corporate profits to be made in the development and deployment of the resulting technologies have been significant factors in the ever larger numbers of technical facilities on foreign soil. These include such things as missile early-warning radar, signals intelligence, space tracking telescopes and laser sources, satellite control, downwind air sampling monitors, and research facilities for everything from weapons testing to meteorology. Missile defense systems and network centric warfare increasingly rely on satellite technology and drones with associated requirements for ground facilities. These facilities have often been established in violation of arms control agreements such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty meant to limit the militarization of space.

The assumption that US bases served local interests in a shared ideological and security project dominated into the 1960s: allowing base access showed a commitment to fight Communism and gratitude for US military assistance. But with decolonization and the US war in Vietnam, such arguments began to lose their power, and the number of US overseas bases declined from an early 1960s peak. Where access was once automatic, many countries now had increased leverage over what the US had to give in exchange for basing rights, and those rights could be restricted in a variety of important ways, including through environmental and other regulations. The bargaining chips used by the US were increasingly sophisticated weapons, as well as rent payments for the land on which bases were established.[9] These exchanges were often become linked with trade and other kinds of agreements, such as access to oil and other raw materials and investment opportunities (Harkavy 1982:337). They also, particularly when advanced weaponry is the medium of exchange, have had destabilizing effects on regional arms balances. From the earlier ideological rationale for the bases, global post-war recovery and decreasing inequality between the US and countries – mostly in the global North – that housed the majority of US bases, led to a more pragmatic or economic grounding to basing negotiations, albeit often thinly veiled by the language of friendship and common ideological bent. The 1980s saw countries whose populations and governments had strongly opposed US military presence, such as Greece, agree to US bases on their soil only because they were in need of the cash, and Burma, a neutral but very poor state, entered negotiations with the US over basing troops there (Harkavy 1989:4-5).

The third period of accelerated imperial ambition began in 2000, with the election of George Bush and the ascendancy of a group of leaders committed to a more aggressive and unilateral use of military power, their ability to do so radically precipitated and allowed by the attacks of 9/11. They wanted “a network of ‘deployment bases’ or ‘forward operating bases’ to increase the reach of current and future forces” and focused on the need for bases in Iraq: “While the unresolved conflict with Iraq provides the immediate justification, the need for a substantial American force presence in the Gulf transcends the issue of the regime of Saddam Hussein.” This plan for expanded US military presence around the world has been put into action, particularly in the Middle East, the Russian perimeter, and, now, Africa.

Pentagon transformation plans design US military bases to operate even more uniformly as offensive, expeditionary platforms from which military capabilities can be projected quickly, anywhere. Where bases in Korea, for example, were once meant centrally to defend South Korea from attack from the north, they are now, like bases everywhere, meant primarily to project power in any number of directions and serve as stepping stones to battles far from themselves. The Global Defense Posture Review of 2004 announced these changes, focusing not just on reorienting the footprint of US bases away from Cold War locations, but on grounding imperial ambitions through remaking legal arrangements that support expanded military activities with other allied countries and prepositioning equipment in those countries to be able to “surge” military force quickly, anywhere.

The Department of Defense currently distinguishes between three types of military facilities. “Main operating bases” are those with permanent personnel, strong infrastructure, and often including family housing, such as Kadena Air Base in Japan and Ramstein Air Force Base in Germany. “Forward operating sites” are “expandable warm facilit[ies] maintained with a limited U.S. military support presence and possibly prepositioned equipment,” such as Incirlik Air Base in Turkey and Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras (US Defense Department 2004:10). Finally, “cooperative security locations” are sites with few or no permanent US personnel, which are maintained by contractors or the host nation for occasional use by the US military, and often referred to as “lily pads.” In Thailand, for example, U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield has been used extensively for US combat runs over Iraq and Afghanistan. Others are now cropping up around the world, especially throughout Africa, as in Dakar, Senegal where facilities and use rights have been newly established.

Critical observers of US foreign policy, Chalmers Johnson foremost among them, have thoroughly dissected and dismantled several of the arguments that have been made for maintaining a global military basing system (Johnson 2004). They have shown that the system has often failed in its own terms, that is, it has not provided more safety for the US or its allies. Johnson shows that the US base presence has often created more attacks rather than fewer, as in Saudi Arabia or in Iraq. They have made the communities around the base a key target of Russia’s or other nation’s missiles, and local people recognize this. So on the island of Belau in the Pacific, site of sharp resistance to US attempts to install a submarine base and jungle training center, people describe their experience of military basing in World War II: “When soldiers come, war comes.” Likewise, on Guam, a common joke has it that few people other than nuclear targeters in the Kremlin know where their island is. Finally, US military actions have often produced violence in the form of blowback rather than squelched it, undermining their own stated realist objectives (Johnson 2000).

Gaining and maintaining access for US bases has often involved close collaboration with despotic governments. This has been the case especially in the Middle East and Asia. The US long worked closely with the dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, to maintain the Philippines bases, with various autocratic or military Korean rulers from 1960 through the 1980s, and successive Thai dictators until 1973, to give just a few examples.

Marcos and Nixon

Conclusion: The World Responds

Social movements have proliferated around the world in response to the empire of US bases, with some of the earliest and most active in the Asia Pacific region, particularly the Philippines, Okinawa, and Korea, and, recently, Guam.[10] In defining the problem they face, some groups have focused on the base itself, its sheer presence as out of place in a world of nation states, that is, they see the problem as one of affronts to sovereignty and national pride.

Demonstrators link hands encircling the US base at Kadena, Okinawa

Others focus on the purposes the bases serve, which is to stand ready to and sometimes wage war, and see the bases as implicating them in the violence projected from them. Most also focus on the noxious effects of the bases’ daily operations involving highly toxic, noisy, and violent operations that employ large numbers of young males. For years, the movements have criticized confiscation of land, the health effects from military jet noise and air and water pollution, soldiers’ crimes, especially rapes, other assaults, murders, and car crashes, and the impunity they have usually enjoyed, the inequality of the nation to nation relationship often undergirded by racism and other forms of disrespect. Above all, there is the culture of militarism that infiltrates local societies and its consequences, including death and injury to local youth, and the use of the bases for prisoner extradition and torture.[11] In a few cases, such as Japan and Korea, the bases entail costs to local treasuries in payments to the US for support of the bases or for cleanup of former base areas.

The sense that US bases impose massive burdens on local communities and the nation is common in the countries where US bases are most ubiquitous and of longest-standing. These are places where people have been able to observe military practice and relations with the US up close over a long period of time. In Okinawa, most polls show that 70 to 80 percent of the island’s people want the bases, or at least the Marines, to leave: they want base land back and they want an end to aviation crash risks, an end to prostitution, and drug trafficking, and sexual assault and other crimes by US soldiers (see Kozue and Takazato, this volume; Sturdevant & Stoltzfus 1993).[12] One family built a large peace museum right up against the edge of the fence to Futenma Air Base, with a stairway to the roof which allows busloads of schoolchildren and other visitors to view the sprawling base after looking at art depicting the horrors of war.

In Korea, many feel that a reduction in US presence would increase national security.[13] As interest grew since 2000 in reconciliation with North Korea, many came to the view that nuclear and other deterrence against North Korean attack associated with the US military presence, have prevented reunification. As well, the US military is seen as disrespectful of Koreans. In recent years, several violent deaths at the hands of US soldiers brought out vast candlelight vigils and other protest across the country. And the original inhabitants of Diego Garcia, evicted from their homes between 1967-1973 by the British on behalf of the US, have organized a concerted campaign for the right to return, bringing legal suit against the British Government (see Vine 2009). There is also resistance to the US expansion plans into new areas. In 2007, a number of African nations balked at US attempts at military basing access (Hallinan 2007). In Eastern Europe, despite well-funded campaigns to convince Poles and Czechs of the value of US bases and much sentiment in favor of taking the bases in pursuit of solidifying ties with NATO and the European Union, and despite economic benefits of the bases, vigorous protests including hunger strikes have emerged (see Heller and Lammerant, this volume).[14]

In South Korea, bloody battles between civilian protesters and the Korean military were waged in 2006 in response to US plans to relocate the troops there. In 2004, the Korean government agreed to US plans to expand Camp Humphries near Pyongtaek, currently 3,700 acres, by an additional 2,900 acres.

Farmers and supporters vigil, Pyongtaek

The surrounding area, including the towns of Doduri and Daechuri, was home to some 1,372 people, many elderly farmers. In 2005, residents and activists began a peace camp at the village of Daechuri. The Korean government eventually forcibly evicted all from their homes and demolished the Daechuri primary school, which had been an organizing center for the resisting farmers.

Korean farmer resisting police eviction to make way for a base

The US has responded to anti-base organizing, on the other hand, by a renewed emphasis on “force protection,” in some cases enforcing curfews on soldiers, and cutting back on events that bring local people onto base property. The Department of Defense has also engaged in the time-honored practice of renaming: clusters of soldiers, buildings and equipment have become “defense staging posts” or “forward operating locations” rather than military bases. The regulating documents become “visiting forces agreements,” not “status of forces agreements” or remain entirely secret. While major reorganization of bases is underway for a host of reasons, including a desire to create a more mobile force with greater access to the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, the motives also include an attempt to derail or prevent political momentum of the sort that ended US use of Vieques and the Philippine bases. The US attempt to gain permanent basing in Iraq foundered in 2008 on the objections of forces in both Iraq and the US (see Engelhardt, this volume). The likelihood that a change of US administration will make for significant dismantling of those bases is highly unlikely, however, for all the reasons this brief history of US bases and empire suggests.

Catherine Lutz is Research Professor at the Watson Institute for International Studies and Professor of Anthropology at Brown University. This article is the revised and condensed introduction to The Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle against US Military Posts (ed.). London: Pluto Press and New York: New York University Press (with The Transnational Institute), 2009.

Posted at The Asia-Pacific Journal on March 16, 2009.

Recommended citation: Catherine Lutz, “US Bases and Empire: Global Perspectives on the Asia Pacific,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12-3-09, March 16, 2009.

Sources

Aguon, Julian (2006) Just Left of the Setting Sun (Tokyo: Blue Ocean Press).

Baker, Anni (2004) American Soldiers Overseas: The Global Military Presence (Westport, CT: Praeger).

Bello, Walden, Hayes, Peter and Zarsky, Lyuba (1987) American Lake: Nuclear Peril in the Pacific (New York: Penguin).

Blaker, James R. (1990) United States Overseas Basing: An Anatomy of the Dilemma (New York: Praeger).

Bloomfield, Lincoln P. (2006) Politics and Diplomacy of the Global Defense Posture Review. In Reposturing the Force: U.S. Overseas Presence in the 21st Century. Carnes Lord, ed. (Newport: Naval War College).

Blum, William (1995) Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions since World War II (Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press).

Campbell, Kurt M. and Ward, Celeste Johnson (2003) ‘New battle stations?’ Foreign Affairs, Vol. 82, No.5.

Castro, Fanai (2007) Health Hazards: Guam. In Outposts of Empire, Sarah Irving, Wilbert van der Zeijden, and Oscar Reyes, eds. (Amsterdam: Transnational Institute).

Cheng, Sealing (2003) ‘”R and R” on a “Hardship Tour”: GIs and Filipina Entertainers in South Korea,’ National Sexuality Resource Center. Available online.

Cliff, Roger and Shapiro, Jeremy (2003) The Shift to Asia: Implications for U.S. Land Power. In The U.S. Army and the New National Security Strategy, Lynn E. Davis and Jeremy Shapiro, eds. (Santa Monica, CA: RAND).

Cooley, Alexander (2008) Base Politics: Domestic Institutional Change and Security Contracts in the American Periphery (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press).

Davis, Lynn E. and Shapiro, Jeremy eds. (2003) The U.S. Army and the New National Security Strategy (Santa Monica, CA: RAND).

Department of Chamorro Affairs (2002) Issues in Guam’s Political Development: The Chamorro Perspective (Guam: Department of Chamorro Affairs).

Diaz, Vicente (2001) Deliberating Liberation Day: Memory, Culture and History in Guam. In Perilous Memories: the Asia Pacific War(s). Takashi Fujitani, Geoff White and Lisa Yoneyami, eds. (Durham: Duke University Press).

Donnelly, Thomas et al. (2000) Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century. A Report of The Project for the New American Century. http://www.newamericancentury.org/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf. Date last accessed Oct. 8, 2007.

Dower, John (1987) War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon Books).

Erickson, Andrew S. and Mikolay, Justin D. (2006) A Place and a Base: Guam and the American Presence in East Asia. In Reposturing the Force: U.S. Overseas Presence in the 21st Century. Carnes Lord, ed. (Newport: Naval War College).

Gerson, Joseph and Birchard, Bruce (1991) The Sun Never Sets (Boston: South End Press).

Gusterson, Hugh (1999) ‘Nuclear weapons and the other in the Western imagination,’ Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 14, No.1, pp. 111-143.

Harkavy, Robert E. (1982) Great Power Competition for Overseas Bases: The Geopolitics of Access Diplomacy (New York: Pergamon Press).

—— (1989) Bases Abroad: The Global Foreign Military Presence (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

—— (1999) ‘Long cycle theory and the hegemonic powers’ basing networks,’ Political Geography, Vol. 18, No. 8, pp. 941-972.

—— (2006) Thinking about Basing. In Reposturing the Force: U.S. Overseas Presence in the 21st Century. Carnes Lord, ed. (Newport: Naval War College).

Henry, Ryan (2006) Transforming the U.S. Global Defense Posture. In Reposturing the Force: U.S. Overseas Presence in the 21st Century. Carnes Lord, ed. (Newport: Naval War College).

Inoue, Masamichi S. (2004) ‘”We Are Okinawans But of a Different Kind”: New/Old Social Movements and the U.S. Military in Okinawa,’ Current Anthropology, Vol. 45, No. 1.

Irving, Sarah, van der Zeijden, Wilbert and Reyes, Oscar (2007) Outposts of Empire: The Case against Foreign Military Bases (Amsterdam: Transnational Institute).

Johnson, Chalmers (2000) Blowback (New York: Henry Holt).

—— (2004) The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic (New York: Metropolitan).

Kennedy, Paul M. (1987) The Rise and Fall of Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500-2000 (New York: Random House).

Lindsay-Poland, John (2003) Emperors in the Jungle: The Hidden History of the U.S. in Panama. (Durham: Duke University Press).

Lens, Sidney (1987) Permanent War: The Militarization of America (New York: Schocken).

Lumpe, Lora (2002) U.S. Foreign Military Training: Global Reach, Global Power, and Oversight Issues. Foreign Policy in Focus Special Report, May.

Lutz, Catherine (2001) Homefront: A Military City and the American 20th Century (Boston: Beacon Press).

McCaffrey, Katherine (2002) Military Power and Popular Protest: The U.S. Navy in Vieques, Puerto Rico (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press).

Magdoff, Harry (2003) Imperialism Without Colonies (New York: Monthly Review Press).

Magdoff, Harry, Foster, John Bellamy, McChesney, Robert W. and Sweezy, Paul (2002) ‘U.S. Military Bases and Empire’, The Monthly Review Vol. 53, No. 10.

Robinson, Ronald, Gallagher, John and Denny, Alice (1961) Africa and the Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism (London: Macmillan).

Roncken, Theo (2004) La Lucha Contra Las Drogas Y La Proyeccion Militar de Estados Unidos: Centros Operativos de Avandzada en America Latina Y el Caribe (Quito, Ecuador: Abya Yala).

Scanlan, Tom, ed. (1963) Army Times Guide to Army Posts (Harrisburg: Stackpole).

Sherry, Michael S. (1995) In the Shadow of War: The United States Since the 1930’s (New Haven: Yale University Press).

Shy, John (1976) A People Armed and Numerous: Reflections on the Military Struggle for American Independence (New York: Oxford University Press).

Simbulan, Roland (1985) The Bases of our Insecurity: A Study of the U.S. Military Bases in the Philippines (Manila, Philippines: BALAI Fellowship).

Smith, Neil (2003) American Empire: Roosevelt’s Geographer and the Prelude to Globalization. (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Soroko, Jennifer (2006) ‘Water at the intersection of militarization, development, and democracy on Kwajalein Atoll, in the Republic of the Marshall Islands’. MA thesis, Department of Anthropology, Brown University.

Sturdevant, Saundra Pollock and Stoltzfus, Brenda (1993) Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the U.S. Military in Asia (New York: New Press).

Theweleit, Klaus (1987) Male Fantasies: vol. 1. Women, Floods, Bodies, History. Steven Conway, trans. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press).

US Defense Department (2004) Strengthening U.S. Global Defense Posture, Report to Congress (Washington, D.C.).

Van Evera, Stephen (2001) Militarism (Cambridge, MA: MIT). Available [online] at http://web.mit.edu/polisci/research/vanevera/militarism.pdf. Date last accessed Oct. 8, 2007.

Wallerstein, Immanuel (2003) The Decline of American Power (New York: New Press).

Weigley, Russell Frank (1984) History of the United States Army (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press).

Weiner, Tim (1990) Blank Check: The Pentagon’s Black Budget (NY: Warner Books).

Notes

[1] Department of Defense (2007) Base Structure Report: Fiscal Year 2007 Baseline Report, available [online] here. Date last accessed June 5, 2008. These official numbers far undercount the facilities in use by the US military. To minimize the total, public knowledge and political objections, the Department of Defense sets minimum troop numbers, acreage covered, or dollar values of an installation, or counted all facilities within a certain geographic radius as a single base.

[2] The major current concentrations of U.S. sites outside those war zones are in South Korea, with 106 sites and 29,000 troops (which will be reduced by a third by 2008), Japan with 130 sites and 49,000 troops, most concentrated in Okinawa, and Germany with 287 sites and 64,000 troops. Guam with 28 facilities, covering 1/3 of the island’s land area, has nearly 6,600 airmen and soldiers and is slated to radically expand over the next several years (Base Structure Report FY2007).

[3] Funding for the International Military Education and Training (IMET) Program rose 400 percent in just eight years from 1994 to 2002 (Lumpe 2002).

[4] The deadliness of its armaments matches that of every other empire and every other contemporary military combined (CDI 2002). This involves not just its nuclear arsenal, but an array of others, such as daisy cutter and incendiary bombs.

[5] A variety of theories have argued for the relationship between foreign military power and bases and the fate of states, including long cycle theory (Harkavy 1999), world systems theory (Wallerstein 2003), and neomarxism (Magdoff 2003).

[6] Donald Rumsfeld, ‘Department of Defense Office of the Executive Secretary: Annual Report to the President and Congress’, 2002, p. 19, available online. Date last accessed Oct. 8, 2007.

[7] Between 1947 and 1988, the U.S. left 62 countries, 40 of them outside the Pacific Islands (Blaker 1990:34).

[8] Luis Nuno Rodrigues, ‘Trading “Human Rights” for “Base Rights”: Kennedy, Africa and the Azores’, Ms. Possession of the author, March 2006.

[9] Harkavy (1982:337) calls this the “arms-transfer-basing nexus” and sees the U.S. weaponry as key to maintaining both basing access and control over the client states in which the bases are located. Granting basing rights is not the only way to acquire advanced weaponry, however. Many countries purchased arms from both superpowers during the Cold War, and they are less likely to have US bases on their soil.

[10] For other studies documenting the effects of and responses to U.S. military bases’, beyond this volume, see Simbulan (1985); Bello, Hayes & Zarsky (1987); Gerson & Birchard (1991); Soroko (2006).

[11] On the latter, see New Statesman, Oct. 8, 2002.

[12] The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus is a good source on the issues as well.

[13] Global Views 2004: Comparing South Korean and American Public Opinion. Topline Data from South Korean Public Survey, September 2004. Chicago: The Chicago Council on Foreign Relations, The East Asia Institute, p. 12.

[14] Common Dreams, Feb. 19, 2007, available [online] here. Date last accessed Aug. 10, 2007.

Source: http://japanfocus.org/-Catherine-Lutz/3086